InterviewsHeke Ngaru

Maori Perspectives on Surfing

Editor’s Note: The following article is intended to shine a light on a different perspective of the experience of riding waves and our relationship with the environment; it does not necessarily reflect Surf Simply’s opinion on religion.

By and large, surfing has strayed radically from its cultural roots, where wave riding signified a lot more than riding a wave. Part of it is just the way the cookie crumbles; call it evolution. But another part is missing out on the vast and astonishing body of ancestral knowledge left by our predecessors; a knowledge that could be helping the sport grow in a more wholesome and sustainable fashion. It’s not mysticism; it’s the very definition of progress. It’s broadening one’s gamut of experience.

“The sense of freedom of riding a wave, the connection with the elemental forces of the wave, the aesthetics of the surrounding landscape, the social interactions with mates, and the coastal environmental quality all contribute highly to the surfing experience,” wrote Dr Jordan Te Aramoana Waiti, a Maori surfer and Senior Lecturer at Waikato University, New Zealand, in a paper published back in 2019 entitled Kaihekengaru: Maori Surfers’ and a Sense of Place. Now, he has teamed up with Belinda Wheaton to expand on the topic, writing a chapter for The Routledge Handbook of Ocean Space about indigenous Maori past and present relationships with the ocean.

Stretching back to the arrival of Maori to Aotearoa New Zealand from East Polynesia (between 800-1350 AD), Waiti and Wheaton trace the link between Maori and heke ngaru: from how the initial practice of seafood harvesting for nutrition developed into a means of recreation and a dependence on the ocean that came to shape much of Maori society and culture; to the the first documented accounts of Maori riding waves by European explorers in the 18th century; to the arrival of Duke Kahanamoku in 1915 and the rise of surfing popularity in Aotearoa NZ; through to the ways in which Maori have been using heke ngaru to reclaim traditional knowledge and their ‘space’ within the ocean.

“In Aotearoa New Zealand’s ‘post’-colonial political context, contestation over water is not just concerned with issues such as property rights or ‘managerial responsibilities’, but are also ‘deeply felt affective concerns about human-environmental relations’ (Strang, 2014: 124). These are issues of cultural awareness, support and respect for different knowledge systems. Ongoing contestation over rights and responsibilities of and for water and land are deeply embedded in Maori ongoing battle for self-determination. The desire for Maori self-determination through these ocean-based sporting activities can be seen as examples of this ongoing struggle.”

Surf Simply caught up with Dr Waiti to hear his insights on Maori surf culture and how it can positively influence the surf culture at large and the way surfers relate to, respect, and protect the marine environment. Readers who wish to get some context are highly encouraged to read the full chapter here.

In your 2019 paper, you write that, due to the spiritual, genealogical, affective, cognitive and behavioural ties Maori build with a physical location as a result of the meanings and history within it, environments like the ocean are regarded as taonga (treasures). As a Maori surfer yourself, how would you say this view informs the way Maori experience and approach the practice of wave riding? And is this something you hear Kiwi surfers talking about?

Many Maori wave riders will conduct a karakia (incantation) before entering the water to seek protection, and to also acknowledge any combination of deities (e.g.,Tangaroa, Hinemoana, Hineahuone), local ancestors and geographical landmarks (mountains, rivers, streams, etc.), local kaitaiki (spiritual guardians), or family members who have passed on. As well as karakia, Maori may also mihi (formally acknowledge) the nearby sites of significance (ancient villages, ancient sites of cultural customs) and the hau kainga (the local tribe and people) before they enter the water. This is conducted as a sign of respect to the local people and the area’s history.

Whilst out in the water or in the lineup, Maori will often take note of or acknowledge the various kaitiaki (spiritual guardians) that may be about. These may include, but are not limited to stingrays, orcas, other mammals, specific fish species, and coastal birds. The presence of these is often a sign of something positive or negative that may or has occurred. This depends on which tribal area you are in, and which kaitiaki is present.

I don’t think these customs are common amongst Kiwi surfers per se. This is probably due to a lack of knowledge and understanding (e.g. who the local people are, the historical significance of the area, a reverence for indigenous spirituality). Many Kiwi surfers are, however, cognisant of the power of the ocean and the need to respect it when surfing.

How have you witnessed ocean-related Maori traditions change with your generation?

I haven’t really noticed too many changes, except that many Maori (and Maori wave riders) are now conducting non-christian karakia, opting to revert back to our traditional karakia that focused on a variety of deities. Indeed, these are the karakia that served us well for the thousands of years before the arrival of Christianity to Aotearoa NZ.

My first love in regards to the ocean was diving for shellfish and seafood; it was a skill passed down by an uncle of mine when I was 15 years old. Indeed, growing up, our family would gather seafood of various kinds; no matter where we were in Aotearoa, we would seek out the local shellfish to add to our meals. Over the past ten years, there has been a massive resurgence of Maori undertaking freediving, spearfishing and scuba diving – by and large, to harvest food as opposed to sightseeing underwater. This increase in Maori partaking in these activities has been great because it reaffirms our cultural practices (albeit with modern technologies), and customs (i.e., the increase in deity based karakia/incantations). It also reinforces our cultural identity, provides traditional foods, and helps maintain a sense of health and wellbeing (spiritual, cognitive, familial and physical).

What are some of the most significant or common ways in which water-based cultural practices of Maori clash with non-indigenous interests in present-day Aotearoa NZ?

I think the most prominent cultural clash comes with the concept of rahui, which are used to regulate human activity to maintain health and wellbeing, or to protect and conserve resources. I am speaking in general here as different tribes have different rules pertaining to the purpose, use and implementation of rahui. However, for example, should someone drown at a beach then the local tribe may impose a rahui on that beach for a certain number of days. This allows time for the tapu (sacredness) to dissipate, as a form of respect to the family of the deceased, or maybe to protect swimmers from danger. Of course such a restriction on activities can be difficult for say commercial fishermen who make a living from being on the ocean everyday. And for Maori commercial fisherman, this can be a quandary. Another example is when rahui are placed on an area to allow that area to replenish its resources (i.e., shellfish), or to protect the public from waterborne sickness. Whilst there are a handful of fishermen and divers who often oppose such restrictions, believing that they are denied their right to fishing and harvesting, most New Zealanders are cognisant of the need for these resource protection measures.

In the chapter, you recount that Matauranga Maori (Maori knowledge) was traditionally transmitted through leisure and cultural activities (among other things) and that a rupture in this transmission of knowledge would result in fractured kinship structures, diminished connections with the environment and, consequently, an impact on one’s sense of identity. I was wondering if, when thinking of that, any ocean-related anecdotes, personal memories or folk stories come to mind?

Christianity had a major role in the disconnect from our cultural identity. For example, in the far north of New Zealand where my maternal tribal links are, we had to protect our carvings (these carvings held our ancestral knowledge) by burying them because the missionaries despised our polytheistic beliefs. As a result, this knowledge was lost for future generations.

In relation to the ocean, the influence and emphasis of Christianity on monotheism meant that as time went on, many of our people disregarded our various deities when conducting incantations – especially those related to the sea. There are numerous deities and ancestors associated with the ocean: Tangaroa (God of the sea), Hinemoana (the Ocean-maiden), Hine One (personified form of sand), Tawhirimatea (God of Winds). Yet, since colonisation, many Maori sought to conduct Christian-based incantations before entering the sea. This has changed in recent decades though, especially with the reclamation of our double hulled voyaging knowledge, with many Maori now utilising our traditional incantations.

You cite data from Sport NZ which suggests that Maori constituted less than 6% of the total number of New Zealanders that surfed in that given year (2015). In your view, what are some of the main factors that influence such a low number of Maori surfers in comparison to pakeha [New Zealanders primarily of European descent]?

Some tribes in Aotearoa NZ speak of ancestors surfing before they left Hawaiki for Aotearoa NZ. For example, Turi, a common ancestor throughout Polynesia, was also the captain of the Aotea canoe that sailed to Aotearoa NZ. Turi and his wives, Hina-raurea and Hina-arauriki, were well known for their surfing prowess, and so too were Turi’s two sisters. In more contemporary times, Te Rangituataka, a Ngati Maniapoto chief, was observed by British explorers in the late 1800s surfing waves on his two-man canoe. Like the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians), we traditionally rode logs, canoes, planks of wood, as well as poha (inflated kelp bags). So there is a traditional and pre/post European history of Maori surfing. Nevertheless, the climate is temperate here, so surfing or wave riding would have been a strictly summer pastime, and in the South Island even less so.

The low number of Maori surfers began with the colonisation process enacted upon us by the British. During this time period, our priorities had to shift away from traditional village life, where we practised our customs daily, towards holding onto our land, managing the missionaries, surviving the newly introduced diseases, petitioning the government, and fighting off the British invaders. This shifting of priorities, the loss of land, the various legislative measures (i.e., Tohunga Suppression Act 1907) introduced by the colonial government, the corporal punishment received for speaking our language – all led to a breakdown in cultural customs and concepts, poverty and destitution. At the same time, the disdain for surfing held by the missionaries meant surfing wasn’t looked upon favourably.

Despite this, many of the coastal tribes still practised wave riding to various degrees; at least until the post-War years, when urban migration occurred. As more and more Maori shifted into the cities, our ties and knowledge pertaining to the ocean slowly diminished. When surfing became ‘whitewashed’ (i.e., the perpetuation of the ‘bronze Aussie’ and ‘California surfer dudes’), I think it distanced Maori from surfing, in that we couldn’t see ourselves reflected in this pastime. As a result, many Maori believed – and still do – that surfing was a pursuit suited only for Europeans, and had no cultural connection to Te Ao Maori (a Maori worldview). So something we are trying to do with Maori communities is to reclaim our surfing knowledge; to highlight the fact that surfing is a part of our whakapapa (genealogy) from before we left Hawaiki through to our arrival and settlement in Aotearoa NZ.

Throughout that time, and even more so in contemporary times, finances also play a big role through things like purchasing a board and wetsuit, and transportation to the beach. Unfortunately for Maori, we tend to sit at the bottom end of the socio-economic scale here in Aotearoa NZ. Also, Maori place a strong emphasis on kinship, and therefore it is uncommon for Maori to partake in activities without family members. In that sense, role modelling or having parents and other family members who surf has a big impact on whether an individual picks up surfing. Moreover, Maori whanau [Maori-language word for extended family] tend to go to the beach to fish and collect shellfish, seaweed, etc., so mainly for physical and spiritual sustenance. Often when I was growing up, my dad and uncles would complain to me saying I was wasting time sitting out there on a surfboard. Again, a belief that surfing was not a part of our whakapapa.

How is the representation of Maori surfers in Aotearoa New Zealand nowadays? Do you feel opportunities are well-balanced?

There has been an increase in ‘learn to surf’ programmes being delivered throughout Aotearoa, and by and large they are all doing a wonderful job. What is missing however are ‘learn to surf’ programmes framed from a Maori worldview, drawing on Indigenous knowledge, and conducted in full immersion Te Reo Maori (Maori language). I am only aware of ourselves (Aotearoa Water Patrol) who can deliver in Te Reo Maori.

At the other end of the scale, numerous professional Maori surfers have paved the way in the contest scene. In the 1980s, this was led by Maori surfers from Waitara in Taranaki, and then those from the Raglan and Gisborne regions. Airini Mason (Rongomaiwahine) competed well in the Australian Pro Juniors and QS in the late 2000s. In recent times, the first Maori surfer to make the CT was Ricardo Christie (Rongomaiwahine, Ngapuhi) in 2015. At the moment, we have Te Kehukehu Butler (Ngati Ranginui) and Elliot Paerata-Reid (Tuwharetoa) who are doing well on the QS.

Along those lines…How do you see Maori participation in surfing developing in the future?

There are a number of Maori-based organisations that are working to increase participation amongst Maori children and youth. These include Aotearoa Water Patrol, Pipi Surf, Waitara Boardriders Association, and of course the Aotearoa Maori National Surfing Titles. These organisations add an extra element to surfing by drawing on our spiritual connection to the ocean, our cultural customs pertaining to the ocean, and the emphasis on kinship – both physical and metaphorical. Moreover, I have found that when Maori children and youth realise that actually, surfing is a part of our whakapapa (genealogy), it gives them more motivation and confidence to undertake the activity. Like other sports, it is hoped that when parents see the enthusiasm of their children partaking in surfing then they will support them. So I think a combination of introducing the activity early in life, describing the links to our ancestors who surfed, getting parents on board to support the ‘lifestyle’, and the role modelling from our professional Maori surfers, places us in a good position to increase participation amongst Maori.

You also note, in the conclusion of the chapter, that the present cultural and political status of Maori impacts social relations, including those more-than-human. This made me think of two examples from your 2019 paper: the Whanganui River being granted legal personhood and the changes to the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement to provide for Maori involvement in decision-making over iwi (tribal) waters. With that in mind, how would you say tapping into indigenous Maori knowledge benefits these more-than-human relations in Aotearoa NZ?

A Maori worldview sees ourselves as descendants of Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatuanuku (the earth mother). They begat numerous children such as Tane-Mahuta (God of the forest and trees) and Tangaroa (God of the sea), who then begat the specific trees, plants and sealife. So as Maori, we have a direct whakapapa (genealogy) link to the environment; these are our whanau (family), and with it comes the obligations of kaitiakitanga (conservation). And these views are not dissimilar to those of the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) and Kanaka Maohi (Native Polynesians).

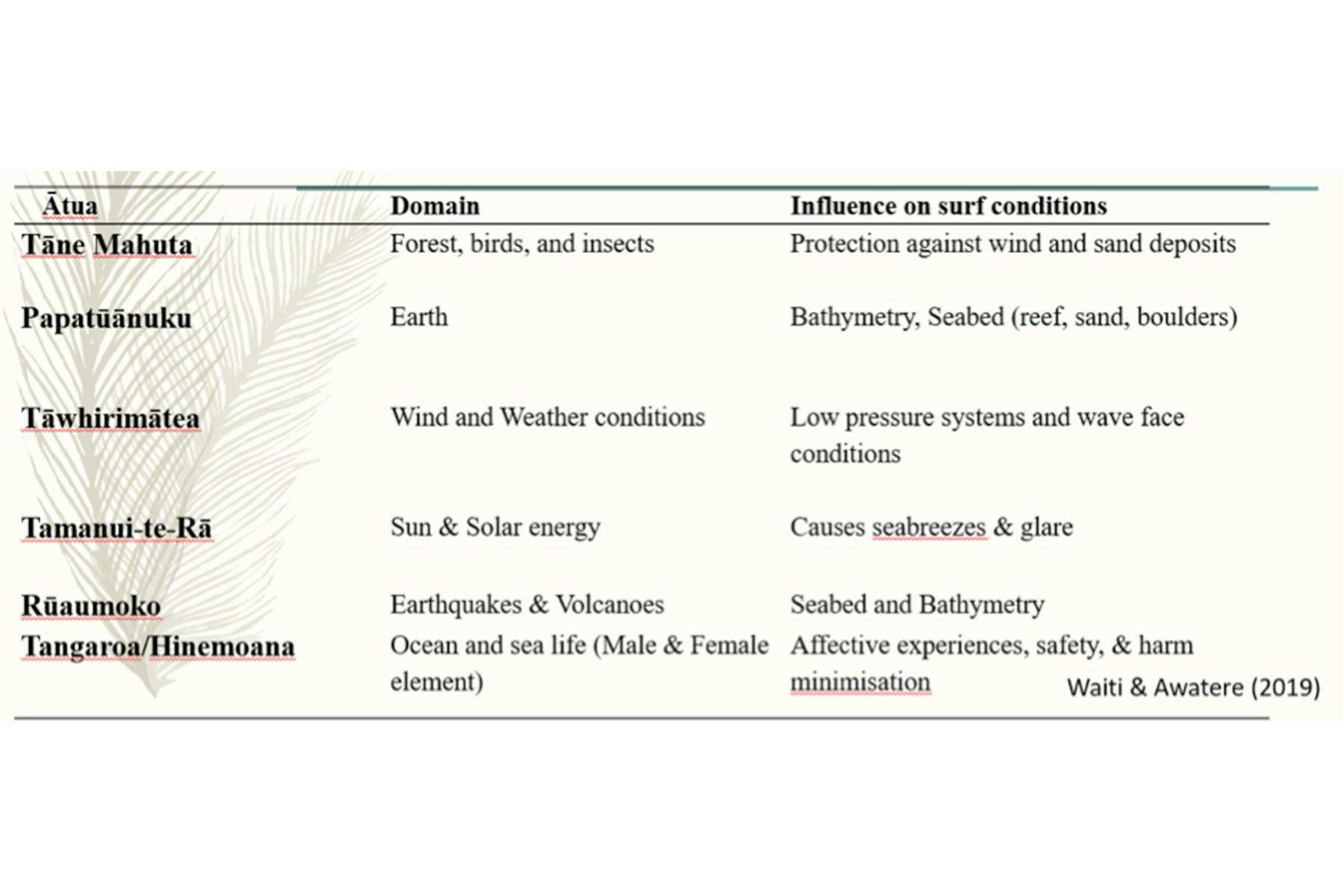

In relation to surfing, I see the influence of these deities on the surf here in Whaingaroa/Raglan.

For example, Tawhirimatea (the god of wind) develops low pressure systems underneath the south island of Aotearoa NZ. This creates the swell that marches up the west coast of both NZ islands and in time reaches the Raglan points. Alongside Tamanui-te-Ra (The Sun), Tawhirimatea also determines whether we have clean faces or not (i.e., sea breezes). The bathymetry of the ‘Raglan Points’ relies on the volcanic rock that is deposited on these points; this was a result of Ruaumoko, the deity of earthquakes and volcanoes. So for Raglan/Whaingaroa, the perfect waves we experience on these points can be attributed to these Maori deities.

People don’t have to necessarily agree with these beliefs. However, it is helpful to respect the knowledge systems of Indigenous people.

Similarly, how could drawing inspiration from matauranga Maori (Maori knowledge) help make the global surf culture richer and more sustainable?

Indigenous cultures throughout the world are the original caretakers of the environment. We see ourselves as a part of the environment – as opposed to being at the top of the pyramid. We are genealogically linked to the trees, the birdlife, the sealife, etc., so we have an obligation to protect them. Nevertheless, there are numerous organisations around the world that are leading in that space. Here in Whaingaroa/Raglan we have KASM (Kiwis Against Seabed Mining), which has managed to achieve some great outcomes here in Aotearoa NZ. In terms of Matauranga Maori in particular, I think the aforementioned rahui could be a useful tool, especially as a form of resource replenishment. Indeed, various Indigenous cultures throughout the world have their own, but similar conservation practices.

Have you got any surf-related projects and/or research in the pipeline?

Myself and some friends have begun an organisation named Aotearoa Water Patrol, where we deliver Matauranga Maori-based water safety programmes for Maori. We were also fortunate to be invited to Hawaii to train under the auspices of Hawaiian Water Patrol and the Honolulu Fire Department – the only New Zealanders to be invited and certified in PWC Surf Risk Management & Rescue Water Craft Operations. We continue to deliver similar courses here in Aotearoa NZ. Over the next year we are looking at developing a learn to surf curriculum that is borne out of Matauranga Maori and is full-immersion Maori language. This will involve reclaiming some of our Maori terms in relation to the surf, and we are hoping to work alongside our revered Ocean Navigation colleagues for some of these terms. We are also working towards developing a Maori youth development programme that focuses on behaviour control, using PWC’s as a teaching medium.

Alongside another Indigenous colleague from the USA, Associate Professor Dr. Nicholas Reo (Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians), we have begun shooting a film that is based on indigenous perspectives of surfing and engaging with the ocean. We began filming just before the pandemic and hope to conclude filming later this year.

In another but similar space, some colleagues and I from the University of Otago are developing a list of water safety competencies for Maori whanau (families). There are 15 widely considered competencies that integrate the physical, cognitive and affective attributes needed to prevent drowning, and these have been developed and tested in pool environments. Our research seeks to adapt and refine these attributes so that they better align with the common water practices undertaken by Maori – which is mainly open water environments (i.e., ocean, rivers, lakes), a specific focus on food gathering activities (i.e, diving, snorkelling, shellfish gathering), and competencies that involve the family as a whole as opposed to individuals (i.e. assisting other family members).

Lately, there has been more and more light cast on Indigenous world views and how they can provide wholesome and sustainable alternatives – or at least a different perspective – to Westernised, Anthropocentric ways of life – especially in the midst of the climate and ecological crisis. How do you see the influences of Indigenous knowledge developing in the future? And in your opinion, how can surfers across the world help make the most of, preserve, and promote the potential that local Indigenous cultures have to offer?

I like to think that future generations will be more open to drawing on Indigenous knowledge when managing the environment and its resources, and developing sustainability and ecological policies. In fact, I have seen this first hand amongst the non-Indigenous students in the University classes that I teach. Each year, more and more of them arrive at University with an increased understanding and awareness of Indigenous values and beliefs. So I think things can only improve in that manner.

Something we are grappling with here in Aotearoa NZ is many people are disregarding Indigenous knowledge, and believing that Western Science holds all the truth. We Maori advocate that Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science must be held in the same regard, at the same level, for they both can complement each other and fill in the gaps – especially so when it comes to conservation.

Indeed, we need to move away from capitalism and consumerism; I don’t know how that would work (circular economies?), but communities need to be empowered to be able to enact localised solutions. At a national level, in recent weeks the Maori Party (one of the political parties here in NZ) has put forward a Legislation Bill to ban all seabed mining here in Aotearoa NZ. It is hoped that they will receive cross-party support for this bill to be enacted. More importantly, any conversations regarding sustainability and the environment must have Indigenous people at the decision-making table, whether that is at a local or a national level.

In reference to our Maori deities, I think the following Maori proverb sums up an Indigenous perspective on the importance of being stewards for our environment: Toit? te marae a Tane-Mahuta, toit? te marae a Tangaroa, toit? te tangata (If the land is well and the sea is well, the people will thrive).

I think surfers throughout the world could spend more time chatting with local indigenous surfers to seek some guidance, and gain more insight into the history of those areas, and any customs or concepts that pertain to the area or being in the ocean. That way people would have a more rounded understanding.

It is important to note however that not all Indigenous surfers are knowledge holders. Nor would some freely share that knowledge, for the fear of cultural misappropriation or bastardisation. Failing that, all surfers should revert back to the long-held values of surfers; that is, a respect for the environment. Fortunately this is still common amongst many surfers today.

**********

The author and Surf Simply would like to thank Dr Jordan Te Aramoana Waiti for his assistance with the article. To learn more about his work at Water Safety New Zealand, watch this video. .