Surf ContestsHarder, Better, Faster, Stronger

How Are Elite Competitive Surfers Affected By Psychological Pressure

“When you think about it, most of the heat is spent sitting in the water or paddling around. There is just so much time for surfers to get into their heads, and they only have very limited chances to change the course of the heat,” says Fabian C. Klingner, the lead author of a paper published this past June in the Journal of Sports Science. Aptly named The Heat is On, the study looked into how the performance of elite competitive surfers is influenced by both situational pressure and previous performance errors, and whether athletes of different skill levels perform differently under pressure.

Fabian and his colleagues watched every one-on-one heat of the 2019 women’s and men’s WCT season. For each attempted wave ride, they annotated data like score, time, surfer name and priority status. They interpreted a total of 6497 actions by 80 international elite surfers (28 women and 52 men), across 445 heats. To check variations in the performance due to skill level, surfers were grouped according to their average placement across events: the top 25% as high-ranking (HR), and the remaining 75% as low-ranking (LR).

Situational pressure was categorised based on two key factors: the time left in the heat and the scoring situation, with surfers' leads or deficits determining the pressure they faced. Performance errors were coded when a surfer failed a paddling attempt and lost priority, received a low wave score (<2.0) with priority and in second place, or committed a priority interference violation — all of which stemmed from suboptimal decision-making or execution, independent of the opponent's actions.

The results were divided into Performance after errors and under pressure and Skill-related differences. Regarding the first, much like previous research has suggested, prior errors did have a significant impact on performance on the following ride — yet situational pressure wasn’t identified as a key hindrance on how surfers performed. In their examination of skill-related differences, Fabian and his team observed that whilst HR outperformed LR in wave scores during the 2019 season, there were no significant interaction effects with pressure levels and previous errors, which indicates both HR and LR were equally unaffected by these factors.

“Due to the various influences of the environment in surfing, it is harder to determine when a decrease in performance was truly caused by the behaviour, movements or choices of an athlete. Nevertheless, the findings confirm that surf performance is to some degree negatively affected by negative performance feedback, regardless of skill level; that is, surfing athletes are potentially negatively affected by the perceived probability of failure (i.e., prior performance errors), meaning practitioners should aim to develop strategies with athletes that break the negative performance feedback loops.”

— Excerpt from the paper

Surf Simply caught up with Fabian to delve further into the findings and hear his takes on how studies like his can shed light on this fundamental yet invisible element in competitive surfing and the ways it affects the human being riding the wave.

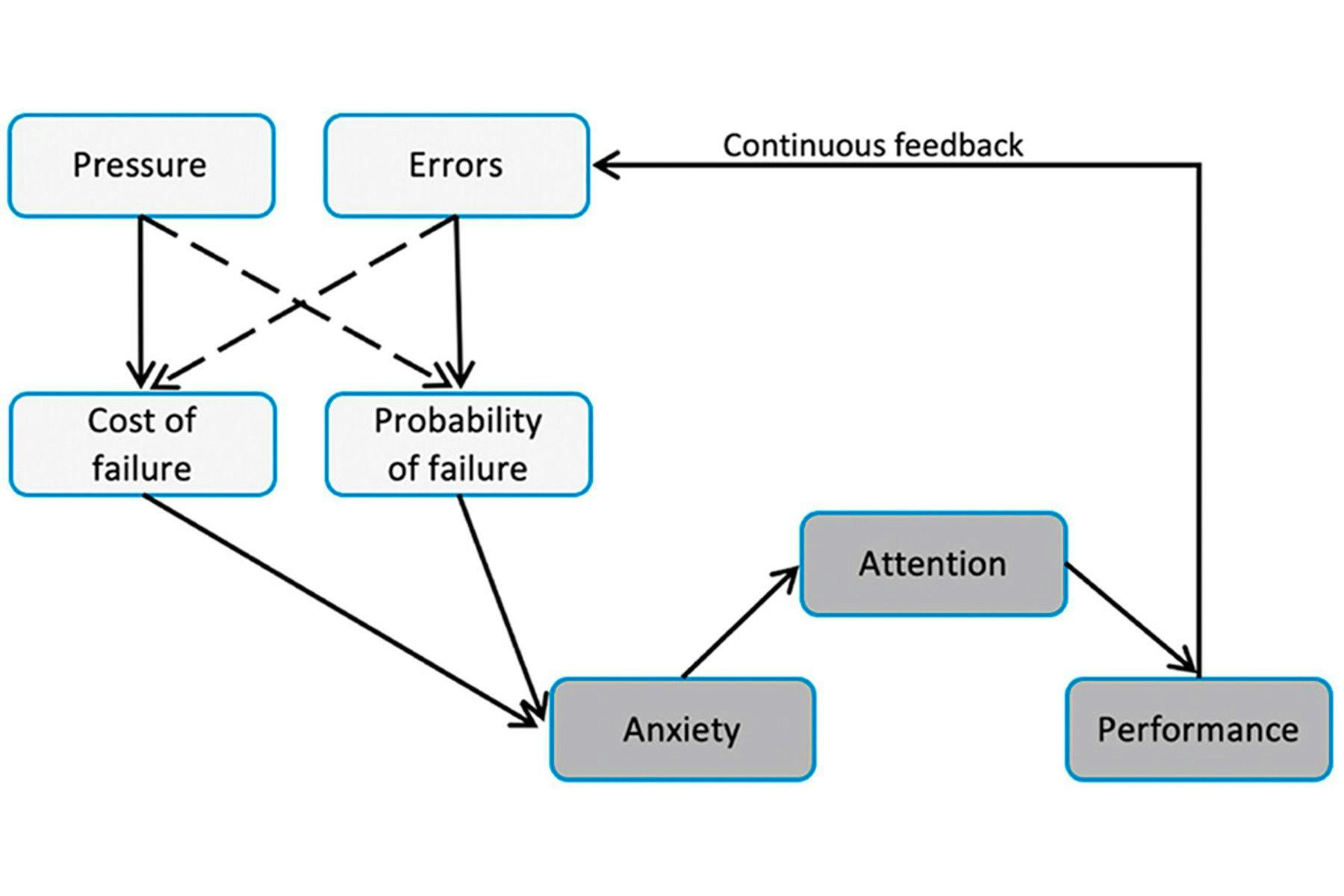

Your study is largely based on the Attentional Control Theory: Sport (ACTS). Could you briefly explain how this theory helps us understand the ways in which pressure and anxiety affect athletes’ performance, particularly surfers?

In a very simplified way, you could say that the ACTS explains how an athlete’s perception of anxiety and pressure is largely based on the interpretation of past failure and the importance of the current situation. A rise in perceived anxiety could then have a negative influence on their performance. For example, imagine a surfer falling on a crucial turn and thus missing a high-scoring opportunity. If this surfer is a low-anxious individual, who doesn’t have certain cognitive biases, they might just paddle back out without spending much thought on the missed opportunity. However, if this were to happen to a high-anxious individual, they might start engaging in conscious error-monitoring, and start wondering why they made this mistake. Especially, if the performance errors start adding up in a competition, high-anxious surfers might start to over-analyse and doubt their own skill set, potentially leading them to believe that they are at an increased risk of failing again. If you now pair this mechanism with high situational pressure — for example when they are in a must-win situation, where re-qualification or even a world title is on the line — then according to the ACTS you have a recipe for high levels of anxiety, which in turn could lead to decreased performance. On the flip side, the model also allows us to identify mechanisms that could lead to perceived pressure, which can be the key to helping those athletes perform when it counts.

The study analysed the interplay between various contextual factors — namely Situational pressure, Priority rule, Performance errors, and Wave Type — and their effects on wave scores and therefore surfers’ performance. Was there a specific factor that was found to be the most impactful?

There were a few contextual factors that all had a significant effect on wave scores. For example, the wave type influenced wave scores, with higher scores being awarded at point and reef breaks compared to beach breaks. Also, having priority is generally associated with higher wave scores, which was to be expected. Interestingly, gender also made a difference, with female surfers generally receiving higher scores than men. But all in all, there wasn’t really one single factor that seemed to have had a bigger impact than others.

Regarding the findings on Performance after errors and under pressure, you write: “...having made a performance error on the previous wave ride is a significant predictor of a decrease in subsequent performance, while pressure is not.” Then, in the Discussion section, you add that, due to the large performance variability and various external influences, surfers might be inherently used to uncertainty, and therefore tend to attribute their competitive situation to external conditions more than personal failure, which in turn helps them preserve their confidence throughout the heat.

That certainly was the most interesting finding of this study, because it is quite contrary to previous research. However, before we can claim that surfers are not influenced by pressure there is still a lot more research needed. I believe that there are so many nuances and layers to the pressure-performance relationship in surfing. For example, we might need better performance metrics that account for the quality of the wave, before we can truly see whether a surfer’s performance is affected by situational pressure. As it stands, in ocean-based surfing, wave scores are heavily influenced by the quality of the wave, and therefore a low score doesn’t necessarily mean that the surfer didn’t perform well on it. However, if one day we have more research, and we still see a tendency of surfers not being affected by pressure, then we should look at why that might be the case. As mentioned in our study, it could in fact be that the ocean and its unpredictability may strengthen surfer’s resilience. Maybe because you can always blame the ocean for not providing enough scoring opportunities. Or because there is always hope for one last set-wave, and because in surfing an athlete is never further away than two waves from winning a heat.

On Skill-related differences, you found that there were differences in performance between high-ranking and low-ranking surfers, but these differences were not influenced by situational pressure or prior performance errors. What insights can we draw from this observation?

This observation might add some weight to findings by Harris et al (2021), who argue that compared to their opponents, the most successful athletes seem to perform better in clutch moments, simply because of their general superiority, and not because they are unaffected by pressure. Such statements basically claim that the concept of “clutch performance” is rather a cognitive bias of the viewer. With that being said, we can still imagine that there are individuals who deal more efficiently with pressure than others. In our study for example, we only grouped the surfers in high-ranking and low-ranking athletes. This of course could mask that there are certain individuals in either of those two groups, who perform much better in high-pressure situations, due to their psychological skill set.

Given the potential impact of prior errors, how might elite surfers adapt their training routines or mental strategies to better handle high-pressure situations during competitions? And would you say these could be applied to amateur surfers as well?

Before we can apply specific strategies for dealing with pressure, it is important to understand that the pressure-performance relationship is often mediated by the cognitive biases an athlete has. For example, what does an athlete under pressure pay attention to, and how do they interpret pressure. And there are large differences between athletes. As mentioned earlier, one athlete might not even react to a missed scoring opportunity, while another, who is more prone to negatively interpreting mistakes, starts to dwell on the mistake and what it could mean for their subsequent performance.

The ACTS gives us two options to help athletes deal with such challenges. First, athletes (elite and amateurs) can learn to maintain a rational interpretation of high-pressure situations in competitions, for example through rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT), and other interventions that improve self-awareness and emotional control. And secondly, they can improve their attentional control, which would allow them to focus on the task at hand instead of letting pressure and anxiety disrupt their attention.

Research has shown that forms of exposure therapy, where athletes train with high levels of anxiety can greatly help them in improving performance under pressure, through improved attentional control. The more you expose athletes to high-pressure situations the more they will get comfortable and adapt accordingly. This could for example be done through specific interventions, mock-heats and participating in actual competitions, ideally with a professional sports psychologist at hand.

If situational pressure doesn't seem to have a significant effect on performance in elite surfing, do you believe this could have implications for how competitions are structured, judged, or evaluated in terms of performance metrics?

As mentioned earlier, I think it’s still a bit too early to claim that pressure doesn’t influence surfing performance. I recall that, especially around the Surf Ranch Pro events, a lot of surfers actually addressed how intense the pressure gets for them. That might be specific to wave pools, where opportunities are incredibly limited, or it might be an elevated feeling of pressure that is also present in ocean-based surf competitions.

I think regardless of any changes that could be made to performance metrics, or the structure of competitions, as long as there are incentives for athletes to be better than their opponents, there will always be an element of pressure. I think sometimes, we should also aim to not artificially increase the pressure too much just for the sake of entertainment. The mid-season cut in the WSL for example creates a lot of drama, which might be entertaining to watch. However, it could also be detrimental to the sport if by doing so we sacrifice the health of athletes, who either drop out during their prime, or might compete injured just to stay on tour. I think it also is less exciting for the viewer to see suboptimal performance. We’ve heard a few surfers say that they can only really “let loose” and surf at their best, after they’ve survived the mid-year cut. And then we get to a point where we might have added more drama to the events, but only at the cost of peak performance, because surfers are trying to play it safe.

In the Discussion, you touch briefly on how future research could “focus on performance under pressure in a competitive environment where surf conditions are more consistent (i.e., artificial wave pools)” in order to decrease the influence of environmental and tactical factors and provide a more detailed analysis of the impact that previous errors and psychological pressure on the performance of surfers.” I was wondering if you could comment on how new technologies, such as artificial wave pools or VR training, might affect the way elite athletes are influenced by psychological factors.

I believe that these kinds of technologies will only help surfers to deal with psychological pressure. We’ve heard many times that surfers feel more pressured in wave pools, because they know that scoring chances are limited. In the ocean, there’s always hope for one last set before the buzzer, if you are still looking for a score. But in wave pool competitions it’s “do or die” from beginning to end. So having this kind of environment can teach athletes to manage pressure in a more efficient way. As mentioned earlier, there is a ton of research that shows that exposure to stress can actually help athletes to become better at dealing with it. So, the more competitions or mock heats they have in wave pools, or even in VR, the more they will be able to adapt and excel.

What would you say are the main takeaways from this study? And how would you like this area of research to develop in the future?

I think one of my takeaways is that the connection between pressure and performance is complex, and to truly uncover these mechanisms in surfing we should try to develop better performance metrics. But I am hopeful that there will be more research on the psychological aspects of surfing. It’s also good to see that the perception of sport psychology is changing in the world of surfing. More and more athletes are now working with professionals and are transparent about the intense pressure they often experience in and out of the water. In the long run, this can only be beneficial to the development of competitive surfing.

*****

The author and Surf Simply would like to thank Fabian C. Klingner for his assistance with this article.